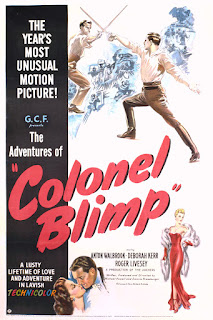

Directed by Gerald Thomas; produced by Peter Rogers

No one in the movies seemed to be entrapped by circumstances as often as John Mills. Sometimes he’s at a disadvantage due to emotional trauma, as in the thriller The October Man; sometimes, he’s foolish enough to become involved with the wrong crowd, as in the excellent The Long Memory. In The Vicious Circle, he does nothing wrong himself, but is caught in a tightening noose nonetheless.

Howard Latimer (Mills) is a successful doctor who receives a telephone call from a friend asking for a favour. He agrees to escort a visiting German actress from London Airport to her hotel. That simple task becomes the first step in a maddening descent when he finds the woman in his apartment, dead. Investigating the homicide is a dogged Scotland Yard detective (Roland Culver), while hovering in the background is a sinister alleged reporter (Lionel Jeffries) and a possible blackmailer (Wilfred Hyde-White).

Initially, The Vicious Circle has the feel of a minor but satisfying thriller. The ordinary man, minding his own business, is quickly swept up in mystery and danger. The elements are there and they are decently handled. There is an aspect, however, of British movies of this sort that is different than in their American counterparts. In the latter, the police are almost always fooled into believing the protagonist is guilty, guilty of something. The British police are usually given more credit and, at the least, are often sceptical of the evidence pointing to the innocent man, evidence that seems too neat and convenient. This aspect frequently provides an entertaining secondary character, the police investigator, who keeps popping up.

In The Vicious Circle, this aspect is carried to an extreme. The police are almost omniscient, ubiquitous. There comes a point when the viewer realises that Mills is not in any real danger from the law. This drops the suspense to nearly nil. It does not ruin the film, but it does change it. It moves from what may have been a Hitchcockian movie (which I don’t believe was the producer’s intention) to something akin to a lighter Agatha Christie crime adventure, like one of her early stories which doesn’t feature her regular detectives. In this vein, The Vicious Circle is a good evening’s entertainment, but if the viewer is expecting something different, an expectation perhaps created by the first third or half, then there is room for disappointment.

The best feature is the puzzle of who is who and what is what. The script does keep the viewer guessing as to who may be trusted, and makes even the characters with straightforward identities doubtful. But it goes too far in some respects. Hyde-White’s character, for instance, behaves in a mysterious fashion when he need not do so at all.

John Mills’s increasingly desperate attempts to pull himself out of a trap into which he’s fallen are always watchable, and the story in this case is certainly intriguing, even if it does become less and less credible. So, while The Vicious Circle isn’t as good as it could have been, it’s enjoyable, if you just let it take you to its inevitable conclusion.