Directed

by Ridley Scott; produced by David Puttnam

Armand

d’Hubert (Keith Carradine), a young staff officer in Napoleon’s army, has the

unenviable task of summoning a fellow officer, Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel), to

a disciplinary interview with their general. Feraud, angered at what he

perceives to be the injustice of the message, conceives an immediate dislike

for the messenger and, despite the subject of his summons being the duel he

fought that morning, challenges d’Hubert there and then to another duel. Thus

begins a sixteen-year saga of obsession and combat, as Feraud and d’Hubert

fight a battle whenever they meet. Only the death of one gentleman – or of both

– will end their ordeal.

Those

who know director Scott from his science fiction works (eg. Alien, Blade Runner) or his action

flicks (eg. Black Hawk Down) might be

surprised that his first feature film was this historical drama, a small epic,

based on a Joseph Conrad story. That story was itself based, remarkably, on

truth: the twenty year running duel between two French Army officers. And while

Scott went on to direct excellent movies, including others with historical

subjects (eg. Kingdom of Heaven), The Duellists must remain one of his

best.

The

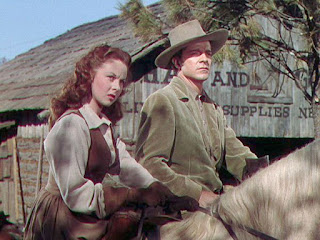

first thing one notices is the film’s beauty. Undoubtedly, Scott and his

cinematographer, Frank Tidy, were inspired by the paintings of the late

classical era. Outside scenes resemble landscapes, interior shots still-lifes

and portraits. The colours are rich and the textures are almost palpable. The

lighting is that of a worker in oils as much as a director of celluloid.

The

illusion of time and place is aided immeasurably by the detail. The costumes,

especially, are exacting and realistic, to which close-ups will testify. The

sets are also true to life; they should be: to limit his budget Scott used

existing structures.

The

casting might seem very odd. Two American actors, Keitel particularly familiar as

rough, urban men, could at first come across as misplaced. This is not borne

out by their performances. The Al Pacino film Looking for Richard demonstrated to me for the first time, even

though it was a documentary, that Americans could effectively portray

Shakespearean characters, even using their every-day accents. The Duellists does the same for

Americans playing Europeans of a couple of centuries ago. Ability and a good

script will do much in the way of credibility. In this case, they are assisted

by the fact that the French revolutionary army, and its successor, Napoleon’s

army, were filled with officers, indeed, generals, whose humble origins would

have kept them privates or corporals in the old royalist army.

Backing

up the leads are a host of excellent actors, mainly in small roles (Robert

Stephens, Tom Conti, Albert Finney, Edward Fox, Pete Postlethwaite (in his first role, a

non-speaking bit as a valet shaving Stephens) and Stacy Keach as the narrator).

The

characters are, perhaps, the weakest element of the movie. Of Keitel’s, we

learn almost nothing, though that in itself may tell us something. We see him

living for his duels; one of the few times we view him doing something else, it

is arm-wrestling, and even here, he demands a re-match when he loses to a

comrade. There are moments of note, however, as when Feraud, at a low point in

his fortunes, watches, as if for no reason, a dog tied to the back of a cart,

forced to trot along to someone else’s commands. Carradine’s d’Hubert is more

rounded: he is, really, an introvert, content with a few friends, astounded,

and appalled, by his growing fame as a ‘man of reputation’, a ‘fire-eater’, a

fearsome duelist. A conscientious officer, he is just as happy in peaceful

domesticity.

The

direction, aside from the settings and backgrounds, is spot-on. Interspersed

with calm, almost still moments – a dinner in a tavern, a couple speaking

quietly of home matters – are the duels, some precise and quick, others brutal

and exhausting.

As

an historian – one who is constantly complaining of inaccuracy in films – I found

nothing about which to complain in The

Duellists. The writer paid attention to military processes and habits. The

weapons and uniforms in particular are given attention: d’Hubert and Feraud are

both officers of hussars (a type of light cavalry) but, belonging to different

regiments, their garments are similar with differences. These change through

the years, the tall shako, for instance, giving way to the taller fur busby. The

passing time is shown, in fact, more by fashion than by anything else, as we

watch the action

span the years of Napoleon’s rule, taking the characters from rural France to

frozen Russia. There is no concession to modern sensibilities in The Duellists (it was made in 1977,

after all): people here act as they would have in the early nineteenth century.

Whether

one watches The Duellists for its

history, its action, its beauty or its breadth of romance (in the wider,

original meaning of the word), this movie will satisfy most. It is one of the

best works from one of the best directors.