Directed by Jean Negulesco; produced by Henry Blanke

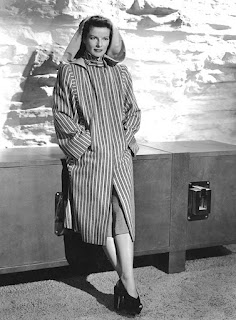

Libby Saul (Ida Lupino) is a shy young woman living with her

parents in a dilapidated farmhouse on the coast of California. Her mother and

father haven’t spoken to each other for years, and the former never leaves her

room. Libby’s only friend is her dog. One day, she goes to view the construction

of a highway near by; some of the men working on it are prisoners from San

Quentin. During a landslide, one of the convicts, Barry Burnette (Dane Clark)

escapes. Feeling an affinity for a person trapped in a life without a future,

Libby assists Barry to get away, hoping to go with him and start afresh

together.

With the inevitability of the story’s ending – at least within the

confines of the 1940s production code – Deep

Valley has to rely on other elements for its appeal, and it’s principally

Lupino on which the movie leans. Lupino, from an historic English acting

family, called herself ‘the poor man’s Bette Davis’. In fact, I think she was,

if not more talented than Davis, rather more versatile. Here, she successfully

passes herself off as a twenty year old girl (she was just about thirty) but,

more than that, confidently portrays a woman who grows strong when given the

possibility of a real future.

It’s in the performances that Deep

Valley has its strengths. Henry Hull and Fay Bainter play Libby’s parents,

and they do an excellent job of creating, initially, two people for whom most

audiences wouldn’t have the time of day. Cliff Saul is a lazy, selfish man who

does the minimum amount of manual labour necessary. Ellie Saul is a

half-hearted hypochondriac whose main emotion is self-pity. Yet, when roused to

fend for themselves, they change and become almost likeable, perhaps reverting

to the young people they once were.

Clark gives a good depiction of a man who keeps trying to do what

is right, but finds his violent nature a constantly destructive force. Wayne

Morris is along as the usual decent fellow the heroine should have fallen in

love with.

What hurts Deep Valley is the script. While the elder Sauls convincingly change for the better, it is due to the actors that we believe this. The script does not provide enough motive. Similarly, Clark’s feelings for Libby – and even hers for him – come across as superficial. Barry and Libby give the impression that they love what each represents to the other, rather than the person. This may very well be the intention of the story (though I doubt it) yet we aren’t shown this aspect. As a result, the audience doesn’t have an investment in the romance.

As well, there is no conflict for Libby between the dangerous

criminal for whom she has fallen and the upright engineer who would be a wiser

match. There really isn’t a purpose given to the latter character.

There is also the strange aspect of the setting. The story is

placed, like the novel by Dan Totheroh, on the coast of northern California,

near Big Sur, where genuine highway construction occurred in the 1930s. There

are references to Monterey, and, as mentioned, San Quentin Prison. The farm, as

may be seen in the opening credits, is on the very shore of the sea, surely

neither a safe nor a productive location for a farm. Yet the film’s title, and

the dialogue, refer to a valley, and to a mountain to which Lupino flees to be

alone. A minor character calls the Sauls ‘hillbillies’. I kept thinking that

the story would have had a bit more credibility if located in the Appalachian

Mountains, or the New England woods. (Thew poster suggests Monument Valley, Arizona...)

Deep Valley, though benefitting from very good

acting, ends by being a predictable, rather turgid drama.