Directed and produced by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

My previous review was of a movie which made heavy use of flashbacks. So it is this time, as well, and the flashbacks are used for a similar reason: to explain the development of a character. But this movie isn’t as well known as A Christmas Carol, and that’s a shame.

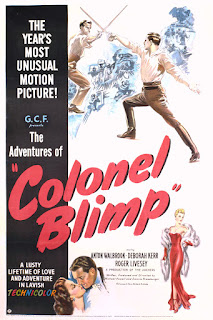

In Britain during the late 1930s and the 1940s, one of the most popular and successful political cartoonists was David Low. Among his creations was Colonel Blimp, the epitome of the blow-hard, unthinking, arch-conservative that Low and many others felt was responsible for the sorry state of Britain, especially in her military preparedness. While many of the latter problems were due to politicians, Blimp came to represent the unreasoning backwardness of many people, whether in the army or not. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (“The Archers”) had the ingenious notion of a story that told how this personality evolved, and they told it in their inimitable style.

The tale opens in 1943 and our Blimp - real name: Major General Clive Wynne-Candy, VC, DSO - has just been humiliated by a forward-thinking, eager young officer. In his rage, Candy bellows, “You make fun of my belly, but you don’t know how I got it. You make fun of my moustache, but you don’t know why I grew it.” And this sets the stage for the flashbacks, which begin in 1902, and we are introduced to Candy, a young subaltern just returned from the Boer War.

As is usually the case with a production by the Archers (see my earlier review of A Canterbury Tale), the success of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp relies not on one aspect of the film, but on many, perhaps all. Most noticeable are the actors and their performances. Roger Livesey, used more than once by the Archers, is a stand-out as the main character, aging forty years in the story’s course, and having to portray the same man at different periods. We hear the voice deepen, the traits grow more pronounced and the gait become more exaggerated. Even so, the verve of the young man is preserved in the old, though in the form that most of us have seen in energetic older fellows.

That Livesey’s role is just one of three important parts is seen by the fact that he actually receives third billing, though he has the most scenes. Significant in Candy’s development is his friendship with a German Army officer, portrayed by Anton Walbrook. His character changes, too, but more sharply than Candy’s. This is the result of the dramatic forces shaping a German gentleman in the first four decades of the twentieth century, forces greater and more violent than those acting on an Englishman. He is not just a foil for Candy’s intransigence, but is his own character, and a reminder of how things can create change whether we want it or not.

The third important role is actually three in itself. Deborah Kerr plays a trio of different women who have a profound effect on Candy’s life. In a way, hers is a difficult series of roles, as her characters aren’t just individual people but are representations of different decades. Kerr portrays these ‘typical women’ splendidly, each having her own personality yet also encapsulating their eras. And she must give her portrayals with less time on-screen (for each of her characters) than the two men.

The script is very good. It has few memorable lines, but creates drama, humour, pathos: feelings, rather than moments. Candy, who could have been a cardboard character, the object of the viewers’ ridicule, is treated sympathetically. Powell and Pressburger rarely make fun of a person for its own sake, and their characters are rarely only two-dimensional, even when we are meant to dislike them (which is itself rare). We see and understand why Candy became the person he did. We see his weaknesses and his strengths. Indeed, the subtlety of the writing is such that some of these are not even mentioned, but implied. For instance, can a man be so inured to change if he accepts and respects women from three eras so contrasting as the 1900s, the 1920s and the 1940s?

The directors display not just their talent for what we see in the foreground, but the detail for which they were famous. The arrangement of the duel is an example: true and accurate, but also interesting. When we see the office of an attaché of the British Embassy in Berlin, we observe, very briefly, a tall stove in the corner; German houses often used these rather than fireplaces before central heating - but how many directors would think to include such a minor item?

The photography is, simply, beautiful. The colour is vibrant and clear. Even in the stills included in this review, one can note the brilliance and detail. It is a pleasure to watch such scenes even if the movie’s subject matter bears no interest. Also to be praised is the make-up. I haven’t seen such convincing ‘old man’ make-up in another movie. It compliments the acting to create a very persuasive illusion of age.

One of a collection of high-quality films from the Archers, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is among my favourite from this talented duo, though the choice is a hard one. A word of warning, though: if you see this film, watch the 163-minute, original edition. There are shorter versions, including one 150 minutes long, which eliminates the framework of the flashback (and thus damages the whole point of the story) and - horrors! - a 90-minute cut. I will leave to your imagination what hacking a 163-minute film down to an hour and a half would accomplish.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is a study of - indeed, a tribute to - a flawed but essentially admirable human being, brought to the screen in an affectionate, sympathetic manner. That, after all, is perhaps how we should view all people; this movie, a plea for understanding, demonstrates that there is more to people, and to their development, than might be easily dismissed.

I've heard the name "Colonel Blimp" still used from time to time, without ever hearing until now the story behind it.

ReplyDeleteI love this line from Wikipedia, incidentally: "Low said he developed the character after overhearing two military men in a Turkish bath declare that cavalry officers should be entitled to wear their spurs inside tanks."

The British Army has been filled with wonderful characters, many more accomplished than the army is given credit for, and quite a few oddities, such as our friend, Alfred Wintle. Fortunately, the latter rarely make it to high command.

Delete