Directed by Jacques Tourneur; produced by Walter Wanger

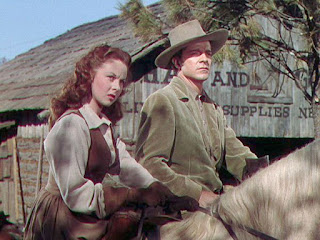

In 1856 Oregon, ambitious entrepreneur Logan Stuart (Dana Andrews) will take any risk for his fledgling transport company. He will also take any risk for a friend, even one like George Camrose (Brian Donlevy), whose business in a mining community is crumbling, just as he is about to marry the beautiful Lucy Overmire (Susan Hayward), who finds Stuart more appealing than her fiance. Add to this a murderous rival (Ward Bond), an incipient Indian war, and a girlfriend (Patricia Roc) with different ideas of their future, and Stuart will be having a busy time…

This early Universal colour western (or ‘northwestern’) has much going for it. The leads are highly watchable, the story has enough threads to weave a saddle-blanket and the action ranges from fist-fights, to shoot-outs, to massacres. The story is a good one, and the script is well-written (adapted from that prolific origin of movie plots, The Saturday Evening Post).

In particular, the characters are well-defined. While Andrews’s role has him as a tough, determined and invincibly loyal friend (even to his own detriment), it is Donlevy’s character that stands out. Camrose is basically a self-destructive man, his otherwise thriving commerce threatened by his incessant gambling, and his romance rocky due in part to his fascination with an acquaintance’s wife (coolly played by Rose Hobart). Yet he is not an unlikeable man, even when driven to homicide. His questioning of another man’s idea of friendship shows that he appreciates its value, and the resignation he feels over his faults is very human.

The other characters are also well-written, too, as is their ambivalence to the local Indians, one settler (Andy Devine), seeing nothing wrong with their dispute with homesteaders, acknowledging that the land is the Indians’, after all, but also being indignant that the Indians resent the settlers.

An interesting aspect of the writing, not entirely satisfactory, is the slightly inconclusive ending. This seems a match for the number of characters who are killed off-screen. Both elements are, of course, realistic: not everything in life ends neatly, and on the frontier, deaths were sometimes known only second- or third-hand. Even so, there is a touch of incompletion to Canyon Passage because of it, however intentional it was on the writers’ part.

The photography is excellent and the direction rightly takes advantage of the then-new colour technology. The location shooting is utilized well. There is tension in a number of scenes, including a kangaroo court’s trial, that shows how precarious life could be on the frontier, even amongst people one thinks of as friends. Stuart’s reaction to a crowd’s enjoyment of his brawl with a rival approaches the contempt that rival has for it, making the viewer see that even in great contrasts, there may be comparisons.

At 92 minutes, Canyon Passage is not a long movie, but it nonetheless conveys a convincing impression of time and distance in the wide spaces of a largely wild land. A miniature epic, it is a western with a different setting, a setting which serves it well and which is, in turn, served well by the movie’s other components. (But no one passes through a canyon - just the opposite, as characters must crest a mountain range in their journeys…)

No comments:

Post a Comment