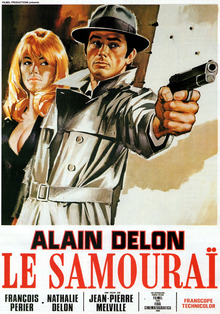

Directed by Jean-Pierre Melville; produced by Raymond Border and Eugène Lépicier

Jef Costello (Alain Delon) is a young assassin-for-hire. His latest job, involving the murder of a night-club owner, goes as planned; he isn’t concerned that is seen by witnesses, as he will depend on their statements' unreliability, and the conflict among their testimony. But one witness, the club’s pianist (Caty Rosier), sees him too closely. Despite this, she clears him with the police of any involvement. He doesn’t know why, and his attempts to discover the truth behind his assignment lead him into unaccustomed danger.

A highly respected and memorable movie from 1960s France, Le samouraï has held up well. It is a good example of a minimalist approach to movies, or at least to what the audience can see and hear. The dialogue is sparse through much of the movie, most of it spoken by the investigating policemen. Exposition is scanty.

There is a problem with Le samouraï, and it is the very light story. It is pretty straightforward. What isn’t explained is left to the viewer’s imagination to fill in. This is not necessarily a bad thing. But the movie then creates a compelling character for its protagonist, and the viewer wants to know more about him, and is deliberately frustrated in this. That is, perhaps, the point of the style, but it may leave some people dissatisfied.

Also a problem are aspects which suggest that not a lot of thought went into reconciling style with substance. For instance, Costello has a large ring of keys that allows him to operate any Citroën car that he cares to steal. That’s a neat idea on the surface, but very impractical. It could take hours for him to find the right key to start his stolen automobile. I suspect that’s why professional car thieves simply ‘hot-wire’ a vehicle in some fashion. As well, Costello is given his firearms by a mechanic-contact; these he uses without, so far as we can see, determining if the ammunition in them is live, or if the weapon works properly. That’s not good preparation for a life-and-death situation.

Delon is excellent in the lead. The epitome of cool, Costello seems always to have been in control of his assignments, of his emotions, and when things go wrong, he fights to maintain that control. He is not entirely successful, yet continues to do things his own way. Rosier fashions a suitably enigmatic foil, equally obscure in motive and thought, while François Périer portrays the top cop on the case as a determined and ruthless law-enforcer.

It is the characters and direction that make the movie, even if much, especially about the protagonist, is left unexplained. We first see Costello lying on a bed in a sparsely furnished room. The fact that there are no books, no radio, no television, no dishes or food, suggest, especially after the viewer spends some time with him, that Costello has no life beyond his periodic deadly assignments.

He has a caged bird; it inadvertently saves his life later, and the few seconds in which Costello looks at the bird as he leaves his apartment says much about the man. There aren’t many people who would assuredly acknowledge a debt in such a silent fashion, and it is a tribute to the acting and direction that the viewer knows immediately that Costello feels more affinity for the bird than for any human in the picture.

While the scanty plot and sparse dialogue may turn some off of Le samouraï, and others will dislike the implausibility of such a hit-man staying alive for long, the movie has enough style and suspense to carry it to its conclusion. It justifiably cemented Delon’s career and, as far as style is concerned, is worth remembering.

This sounds a bit like "The Day of the Jackal," a film I thought was terrific viewing, despite its increasing implausibilities.

ReplyDelete